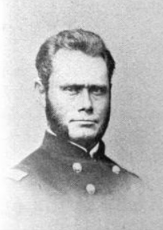

Though unsigned and probably missing a page, I believe this letter to have been written by Lt. Oliver Waldo West (1842-1889) of Co. K, 130th New York Infantry. This regiment was converted to cavalry in August 1863 and called the 19th New York Cavalry. Later it was renamed the 1st New York Volunteer Dragoons. At the time this letter was written, the 130th New York Infantry was attached to Spinola’s Brigade at Suffolk, Virginia, engaged largely in building up the defenses of that village.

Envelope from 1862-3

Oliver was the son of Perry West (1816-1908) and Melissa Carpenter (1812-1885) of North Dansville, Livingston county, New York. He was the Editor of the Livingston Democrat newspaper when he enlisted as a private in Co. K on 31 July 1862. He was quickly promoted to First Sergeant on 3 September 1862 and five weeks later, promoted to 2d Lieutenant. Fortuitously, when the 1st Lieutenant of Co. K resigned on 24 November 1862, Oliver was promoted once again to take his place. Oliver was captured on 7 May 1864 at Todd’s Tavern, Virginia, and exchanged in late April 1865 at Wilmington, N. C., mustering out of the service not long afterward.

Why do I believe this letter was penned by Lt. Oliver West? There are several letters under the title “Sarah Stilson Correspondence” housed at the Hesburg Libraries, Rare Books & Special Collections, University of Notre Dame, many of them written by Lt. West to Sarah Stilson before and during the Civil War. Digital images of Lt. West’s letters are available on line and not only do they look to be in the same hand, they contain many of the same expressions and characteristics. The content is consistent as well, including the defense of Dr. Kneeland, the regimental surgeon [see West’s letter of 31 December 1862].

According to the Hesburg Libraries’ Website, “Oliver Waldo West (b. 1842), a young newspaper editor (and future lawyer) from North Dansville, Livingston County, whom Stilson had met at a teachers’ institute in 1860…The letters exchanged by West and Stilson (16 written by West, 11 by Stilson) are long, lively, and opinionated—often, it would seem, provocatively so. While much of the content is personal news, recounted at length, with frequent touches of humor, the letters are also very much a dialogue, an exchange of ideas and feelings about both contemporary affairs and the broader life of the mind. There is a good deal of commentary on literature; both West and Stilson had a weakness for verse. There is also a good deal of verbal sparring, not least about gender relations.”

TRANSCRIPTION

[Camp near Suffolk, Va.] ¹

[5 November 1862]

….and it was a good thing on the whole as I know in my own case. Although I was oh so tired, weary, footsore, and stiff legged, yet, if we rested 5 or ten minutes and I reclined against the fence or lay right down on the ground (as ¾ of them did, with my rolled blanket for temporary pillow), when the brigade was ordered again, “Forward March” I would be so stiff that I could scarcely move my legs till I got warmed up a little so it was better to toil on, move out and almost ready to drop down with fatigue as one was than to stop often, get chilled through, and stiffened up.

When we arrived within a mile or two of our camp, a little after midnight Friday night, I do declare that if we had been ordered to about face and march back, I don’t believe, hardly, I could have gone over 40 rods without falling out by the wayside as many a tired and sleepy soldier did as it was. But the hope of soon getting home (i.e. into camp quarters) kept us up and we dragged ourselves along into our camp here, staggered into our tents, and dropped down on our beds and rested. Oh! how good it was [ ]! The bed you lay yourself for nightly though never so [ ] and civilized in structure and style, is not so welcome and sweet to you as when our rude camp [ ] to us in the sun all hours of last Saturday morning. For a day or two after we returned, one could tell a “Blackwater Man” almost as as far as he could see him by his halting, limping gait. Coming back, I wore my rubber overcoat and carried strung over my shoulder with the ends tied, my blanket rolled up, besides my loaded haversack and canteen, and my sword belted around my waist and my revolver on the belt. Oh rheumatics—how my shoulders did ache some of the times. It seemed as though I should sink under them. But I kept up. And my case, you must remember, was not exceptional. Hundreds felt as I did. What made it worse for me * was that that was the first “duty” I had done since my sick spell that I referred to in my last. I had been lying still for a couple of weeks and then starting right off on a forced march of 46 or 50 miles naturally used me rather roughly. But I wasn’t going to stay behind in camp on the plea of sickness as long as I could start with my regiment.

It is late. Goodnight.

Thursday morning [November 6, 1862]. I have to take charge of party of fatigue men—choppers—down to Fort Halleck today, and so I cannot finish this now. I will try and get it into the mail tomorrow. It is raining, windy, and nasty today generally. I presume it is cold and snowing up North. But I will put on my rubber overcoat, buckle on my sword, and “trade in.”

Bon jour, mon amie

Thursday night, Nov. 6 [1862]

Well I have returned from my fatigue expedition safe. I had charge of all the men detailed from our regiment and should have also commanded those from the 132nd New York if they had been sent on to my left. Lt. Mc Ardle, Chief Engineer of this Division, sent now over to me soon after & arrived on my ground, in reference to the direction he wanted us to chop and that if the rest were sent over there, I should set them at work, so and so. But the 132nd are a set of unruly devils and got on the ground an hour after we did and quit an hour earlier so they only went into the outer edge next to the railroad track and I farther into the swamp only attended to my own men. Fort Halleck is erected on the left or northern side of the railroad track as you face towards Norfolk and we entered the forest on the south side, after passing the fort 70 or 100 rods. There, extending in nearly a semi-circle south of the fort, lie over 500 acres of forest which are to be chopped and left lying in all ways as obstructions to an enemy and they when so cut will be worth over 100,000 men for any army of the enemy approaching us from the south , southwest, or southeast would require legions of sappers and miners to clear a way through such formidable and impenetrable abatis. A considerable space has already been leveled and standing on a tall stump or fallen trunk there was a pleasant sort of strange excitement in seeing—surrounded as I was with the wilderness—tall, large trees fall crashing away the branches of their fellows and reach the earth with a thundering reverberation, shaking the foundation beneath us.

Where my men were chopping today, it was swampy ground and the further one penetrates into this thick, [ ], low forest, the damper and more swampy and marshy the ground becomes till by and by the very depths of the Dismal Swamp surround you in all its gloomy perfections, the outskirts of it where we were all sufficiently suggestive.

Today is the first time I have ever been out on fatigue since I entered the army and therefore I was entitled to my side of whiskey, Do you want to know whether I took it or not? Find the counterpart to this * star. You will find the answer.

I guess I must, as soon as I can, devote one letter (to you of course and) to a notice for your edification of the forts they are building around Suffolk. Maj. Gen. [John James] Peck certainly seems to intend rendering this place impregnable. And if digging and chopping can make a place impregnable, this should be so [ ] degrees.

Benjamin T. Kneeland, Surgeon of 130th NY Inf.

I remember you spoke of the heartlessness of Dr. [Benjamin T.] Kneeland and in my epistolary fragment I said a little in reply. Although he has a very rough and rude manner and expression, yet I can hardly think him as devoid of heart as you represent for on both our marches ² towards the Blackwater, he often dismounted to let tired or sick men ride, or relieved a weary soldier by taking his gun or overcoat and blanket, or all together. When we halted in the field Friday noon, he was one of the last to come in, on foot, gun on shoulder, having let some soldier ride his horse. Then his untiring efforts to get a decent and comfortable building for hospital purposes do not show want of heart. Only 7 have yet died out of our regiment—one today from Co. I [named William J. Wright], 2 [from] Co. A, [and] 4 [from] Co. E. ³

There are several regiments encamped over across the road from us. Lately they have had funerals and buried their comrades about five rods from the road. As we pass up to the city, we can see them, one after the other perpendicular to the road and parallel. Some with rude head boards, some not. Oh, it looked sad. A military funeral at home for one who died far away in the service is imposing and effective—especially in the city. But when one dies in camp and his comrades go through with the simple but suggestive burial ceremonies—marching…

¹ The camp of the 130th New York Regiment was located on the Edenton road east of Suffolk near the Great Dismal Swamp. This camp proved to be too unhealthy and early in December 1862 the camp was relocated to 1 mile west of Suffolk near the South Quay Bridge over the Nansemond river.

² The first march toward the Blackwater occurred on 3 October 1862. It was a hurried march of about 50 miles with no losses by the 130th New York. The second march was begun on 30 October and ended on 1 November 1862. The second march is the one described in this letter.

³ The seven members of the 130th New York Infantry that had died on or before 6 November 1862 when this letter was written included: Orson Kenyon of Co. E (18 Sep ’62), Stephen Clark of Co. E (26 Sep ’62), Phineas Simmons of Co. A (24 Oct ’62), Orville Hinman of Co. A (26 Oct ’62), Edwin Slocum of Co. A (29 Oct ’62), Addison Caldwell of Co. F (4 Nov ’62), and William Wright of Co. I (5 Nov ’62). And eighth member died before day’s end on 6 November 1862—Albion Bentley of Co. D (6 Nov ’62).

One thought on “1862: Oliver Waldo West to Sarah Stilson”